Mind Games: How Your Brain Handles Deception and Honesty

- neurohub43

- Jan 8, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 11, 2025

By: Hayden Lim Khai Eun

Introduction

Human interactions are full of little truths, half-truths, and, yes, the occasional outright lie. But did you know that our brains handle each of these differently? From “white lies” meant to spare someone’s feelings to outright deception, the way our minds process honesty and dishonesty offers fascinating insights into human behaviour. Thanks to brain-imaging studies, scientists can see exactly how certain areas of the brain light up when we’re truthful or deceptive, suggesting that honesty and lying are far more complex than we might think.

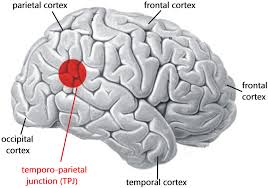

The Brain’s Truth and Lie Processors

When we tell the truth, our brains actually work more efficiently. The prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain behind your forehead responsible for decision-making and moral reasoning—handles this process smoothly. Lying, on the other hand, requires some extra mental effort. Key areas like the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and the insula all jump into action. Each of these brain areas has a specific job: the DLPFC manages behaviour control, the ACC tracks mental conflict (like choosing to lie when we know the truth), and the insula, which is linked to emotion, often gets involved when we feel guilty about lying.

Interestingly, because lying requires more brainpower, we often reveal subtle signs of deception. You might notice someone’s voice slightly change or see them blink more—these are clues that the brain is working hard to “hide” the truth, activating our nervous system in the process.

Why Some People Are Better at Lying

Not everyone lies with the same finesse. In fact, some brains seem more naturally wired for deception than others. Skilled liars often have greater brain connectivity in specific areas, particularly in the orbitofrontal cortex, which controls reward processing and self-control. This extra connectivity helps suppress feelings of guilt or fear of getting caught. These individuals may also have stronger links between the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system (where emotions are regulated), allowing them to push aside nervousness or guilt more easily.

Over time, skilled liars can even “train” their brains to lie with minimal stress, thanks to neuroplasticity—our brain’s ability to adapt and make certain tasks easier. With practice, lying can become nearly as effortless as telling the truth, which may explain why some people seem completely relaxed even when they’re bending the facts.

White Lies vs. Major Lies

Our brains distinguish between “white lies” (like saying you love a friend’s new haircut) and more significant lies (like lying about a mistake at work). White lies, meant to avoid hurting someone’s feelings or sidestep social tension, trigger the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). This area is linked to empathy and social understanding, showing that our brains view these minor deceptions as relatively harmless or even helpful.

On the other hand, major lies—those told for personal gain or to avoid consequences—activate more areas involved in conflict and self-control, such as the DLPFC and ACC. This distinction suggests that our brains have a “deception filter,” allowing us to feel less internal conflict with white lies, while feeling greater stress with more consequential lies.

Detecting Lies: How Hard Is It, Really?

The brain’s complex reaction to lies has inspired truth-detection methods, though reliably detecting deception remains challenging. Traditional lie detectors, or polygraphs, measure physiological responses (like heart rate and sweating) triggered by our nervous system during deception. However, these can be unreliable since nerves can spike even without lying.

More advanced techniques, like fMRI scans, measure brain activity directly, showing us how different regions activate during deception. While promising, this approach faces challenges too: simply being questioned can alter brain activity, and skilled liars can sometimes “beat” the test. Additionally, cultural and individual differences affect how our brains respond to lying, making it tough to define a one-size-fits-all marker for deception.

Honesty’s Reward Circuit

Though lying can be stressful, telling the truth actually activates our brain’s reward system. Honesty triggers a boost of dopamine—the brain’s feel-good neurotransmitter—in areas linked to reward and positive reinforcement, like the ventral striatum. This dopamine release gives us a small “reward” for being truthful, making honesty feel good. And that feel-good factor isn’t just for our own satisfaction; it encourages cooperative, trusting relationships within social groups.

This “honesty reward” effect helps explain why people often feel relieved after confessing a hidden truth. The brain literally reinforces honesty, acting as a subtle motivator to be truthful. That’s good, considering the world of lies we live in today…

Balancing Truth and Deception

At the end of the day, deception and honesty aren’t just moral choices; they’re rooted in complex brain processes that control emotion, decision-making, and memory. Some people’s brains are better equipped for deception, while others feel uncomfortable lying even in small ways. And while white lies get a “pass” from the brain’s conflict centre, bigger lies demand greater cognitive control, resulting in more stress and mental strain.

So, next time you feel tempted to stretch the truth, remember: your brain is probably working harder than you think, balancing social harmony and inner peace like a mental tightrope walker. With every fib or fact, our brains keep pushing us to thread that fine line carefully —trying to keep our friends close, our consciences clear, and our alibis believable.

References

Raden, Aja. The Truth about Lies : The Illusion of Honesty and the Evolution of Deceit. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 2021.

Smith, Rachelle M. Lies: The Science behind Deception. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

“Why We Lie: The Science behind Our Deceptive Ways.” Magazine, 18 May 2017, www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2017/06/lying-hoax-false-fibs-science.html.

Comments