Why Can’t We Look Away? The Neuroscience Behind Love Island

- neurohub43

- Jun 26

- 3 min read

By Katie J

Whether you love it, hate it, or claim to “only watch it ironically,” there’s no denying Love Island is addicting. With dramatic breakups, surprise recouplings, and intense arguments, the show has millions on the edge of their seat. But, why do we care so much about the lives of strangers on reality TV? The answer lies deep inside our brains — in the way we process reward, emotion, and social behavior.

The Dopamine Hit

One major reason we can’t stop watching Love Island is because of dopamine, a chemical messenger, or neurotransmitter in the brain that plays a big role in the reward system. Every time something exciting happens — like a surprise twist or a romantic kiss — our brain releases dopamine, giving us a feeling of pleasure and keeping us wanting more.

Dopamine helps drive motivation and habit-forming behaviors, which is why we get hooked on things that bring instant happiness— like junk food, social media, or yes, reality TV. The show’s constant surprises keep this reward system firing, making you want to watch more to chase that happy feeling (Berridge & Robinson, 2016).

This creates a positive feedback loop: the brain starts associating the show with reward, which makes us crave more of it. According to researchers Berridge and Robinson (2016), dopamine doesn’t just make things feel good — it fuels the drive to seek out more of what gave us that reward in the first place. That’s why Love Island is so addictive, the surprises, drama, and exhilaration constantly reactivate our brain’s reward circuits, keeping us chasing that next hit.

Love Island is designed to trigger these dopamine spikes, especially with its cliffhangers and emotional highs and lows. It’s not just entertainment, it’s brain chemistry.

Mirror Neurons: Feeling What They Feel

Ever feel like you’re right there in the villa, cheering or crying with the islanders? Blame your mirror neurons. These are special brain cells that fire both when we do something and when we see someone else doing it. Basically, they let us “mirror” other people’s emotions and experience empathy.

When a contestant cries after getting dumped or panics during a dramatic twist, our mirror neurons make us feel a little bit of that emotion too. As neuroscientist Marco Iacoboni puts it, mirror neurons “allow us to grasp the minds of others not through conceptual reasoning but through direct simulation” (Iacoboni, 2009). In simple terms: watching drama makes us feel drama — even if it isn’t happening to us.

It’s Human to Care

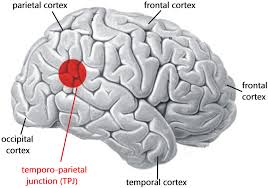

Love Island also grabs us because it’s like peeking into someone’s life. Our brains are curious, and a part called the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is particularly curious about others (Stevens, 2011).

The ACC also reacts when we feel lonely or left out, which may be why watching others connect can feel oddly comforting. With 24/7 cameras showing every flirty chat and sneaky betrayal, the show taps into our need to understand and stay connected to social dynamics.

Love Island might seem like guilty pleasure TV, but our obsession with it comes from something deeply human. We evolved to closely monitor social dynamics because, in ancient hunter-gatherer societies, our survival often depended on our place in the group.

Back then, being part of a tribe meant protection, food, and support. But being excluded could mean danger or even death. That’s why humans developed strong instincts to read others — to figure out who was trustworthy, who might betray us, and who had social power. According to Dunbar (1998), this kind of social intelligence was just as important as physical strength.

Love Island hijacks that ancient instinct. By giving us a front-row seat to real-time emotional conflict, loyalty shifts, and relationship politics, it scratches the same itch our ancestors used to rely on for survival.

Conclusion

So the next time you find yourself watching Love Island until 2 a.m., don’t feel too bad — your brain is just doing what it was designed to do. From dopamine-fueled reward circuits to the empathy powered by mirror neurons, reality TV taps into the very core of how we think and feel. Turns out, the science behind our favourite guilty pleasure is just as fascinating as the show itself.

References:

Berridge, K. C., & Robinson, T. E. (2016). Liking, wanting, and the incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. American Psychologist, 71(8), 670–679. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000059

Iacoboni, Marco. “Imitation, Empathy, and Mirror Neurons.” Annual Review of Psychology, vol. 60, no. 1, Jan. 2009, pp. 653–670, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163604.

Stevens, Francis L., et al. “Anterior Cingulate Cortex: Unique Role in Cognition and Emotion.” The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, vol. 23, no. 2, Jan. 2011, pp. 121–125, neuro.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/jnp.23.2.jnp121, https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.23.2.jnp121.

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1998). The social brain hypothesis. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 6(5), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)6:5<178::AID-EVAN5>3.0.CO;2-8

Comments